IN THIS ISSUE

SUPREME COURT CHEERS FOR COPYRIGHTS IN CHEERLEADING UNIFORMS

TTAB CUTS UP ARGUMENTS FOR SHARPIN REGISTRATION

SUPREME COURT CHEERS FOR COPYRIGHTS IN CHEERLEADING UNIFORMS

Timothy J. Lockhart

In a decision with broad implications for the fashion industry and other industries that combine art with useful articles, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that artistic features of cheerleading uniforms can be copyrighted even if incorporated into the utilitarian designs for such uniforms. Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., ___ U.S. ___, 137 S. Ct. 1002 (2017). Applying separability analysis, the court held that such features are eligible for copyright protection but only if they (1) can be perceived as two- or three-dimensional works of art separate from the useful article and (2) would qualify as protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works if imagined separately from the useful article.

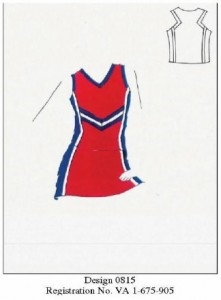

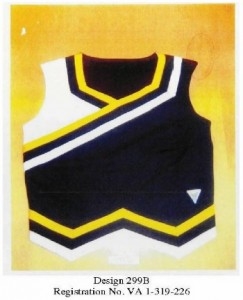

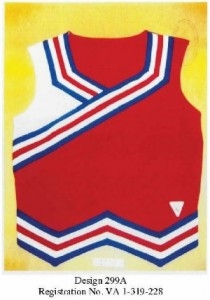

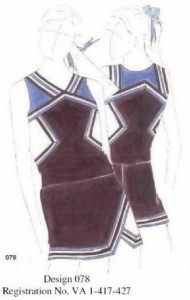

Varsity Brands manufactures apparel, including cheerleading uniforms, and has acquired more than 200 U.S. copyright registrations for two-dimensional decorations that appear on the surface of such uniforms and other garments. The decorations are primarily combinations and arrangements of elements such as chevrons, lines, curves, stripes, angles, diagonals, coloring, and shapes. After Star Athletica advertised cheerleading uniforms displaying similar decorations, Varsity Brands sued for copyright infringement. The district court found for Star Athletica, ruling that Varsity Brands' decorations did not qualify as protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works under U.S. copyright law. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari "to resolve widespread disagreement over the proper test for implementing §101's separate-identification and independent-existence requirements."

Justice Thomas delivered the opinion of the court, in which Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito, Sotomayor, and Kagan joined and Justice Ginsburg concurred. Justice Beyer filed a dissenting opinion, in which Justice Kennedy joined. The court's opinion relies largely on the language of the 1976 Copyright Act, which provides in Section 101 (17 U.S.C. §101) that a "pictorial, graphic, or sculptural featur[e]" incorporated into the "design of a useful article" is eligible for copyright protection if it (1) "can be identified separately from," and (2) is "capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article."

The court said that although the first requirement is not onerous and was readily met in this case, "[t]he independent-existence requirement is ordinarily more difficult to satisfy." The test is whether the feature can "exist as its own pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work as defined in §101 once it is imagined apart from the useful article"-with the caveat that the feature cannot be a useful article or an article that is normally part of a useful article. Stating that this interpretation is consistent with the history of the Copyright Act, the court cited Mazer v. Stein, 347 U.S. 201 (1954), a case decided under the 1909 Copyright Act and involving a copyrightable statuette of a dancer that could be used as a lamp base.

The court held that Varsity Brands' designs also met the independent-existence test. First, the court said, "one can identify the decorations as features having pictorial, graphic, or sculptural qualities." Second, "if the arrangement of colors, shapes, stripes, and chevrons on the surface of the cheerleading uniforms were separated from the uniform and applied in another medium-for example, on a painter's canvas-they would qualify as "two-dimensional . . . works of . . . art" (citing 17 U.S.C. §101). And, the court added, "imaginatively removing the surface decorations from the uniforms and applying them in another medium would not replicate the uniform itself."

The court was careful to note that its opinion did not give any copyright protection to cheerleading uniforms themselves, only to artistic designs such as those at issue in this case. Thus, the court said, Varsity Brands has "no right to prohibit any person from manufacturing a cheerleading uniform of identical shape, cut, and dimensions to the ones on which the decorations in this case appear. [Varsity Brands] may prohibit only the reproduction of the surface designs in any tangible medium of expression-a uniform or otherwise."

Justice Ginsburg wrote a short concurrence in which she said that although she agreed with the court's judgment, she did not believe that application of the separability test was required in this case. "Consideration of that test is unwarranted," she wrote, "because the designs at issue are not designs of useful articles. Instead, the designs are themselves copyrightable pictorial or graphic works reproduced on useful articles."

In his dissent Justice Breyer claimed that Varsity Brands' decorations cannot be perceived as two- or three-dimensional works of art separate from useful articles. He said that in Varsity Brands' copyright applications one sees "only pictures of cheerleader uniforms," which are obviously useful articles. "A picture of the relevant design features, whether separately 'perceived' on paper or in the imagination, is a picture of, and thereby [replicates] the underlying useful article of which [the features] are a part." Therefore, Justice Breyer said, "the design features that Varsity [Brands] seeks to protect are not 'capable of existing independently o[f] the utilitarian aspects of the article'" (citing 17 U.S.C. §101).

The fashion industry has been quick to note this decision and its implications for the future. For example, in an online article published the day after the court released its opinion, Vogue magazine said that "to those inside the fashion world, this was a landmark that has potential to resonate in the industry for years to come" (http://www.vogue.com/article/supreme-court-star-athletica-varsity-brands-ruling-fashion-industry). The article added that although "this ruling isn't a blanket statement protecting all designers from knockoffs and copying," it does open the door "for making the case that certain parts of design can be protected by copyright." That's important, the article observed, "especially considering that Congress has discussed expanding copyright protections for fashion designers but has not yet made [such protections] into law." (sample Varsity Brands copyright registrations appear below)

TTAB CUTS UP ARGUMENTS FOR SHARPIN REGISTRATION

Timothy J. Lockhart

The U.S. Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) has affirmed the refusal to register SHARPIN as a trademark for "cutlery knife blocks which incorporate built-in sharpeners that automatically sharpen knives," in International Class 21. In re Calphalon Corp., Serial No. 86356713 (March 20, 2017) [precedential]. Despite the applicant's amendment of the drawing, or image, of the mark from SHARPIN to SharpIN, the TTAB said that because the applicant had not claimed stylization as a feature of the mark, the amendment had not made the mark distinctive for the applicant's goods.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Examining Attorney assigned to review the application refused registration for the SHARPIN mark under Section 2(e)(1) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(1), on the ground that the applicant's mark was merely descriptive of the goods. In response the applicant amended the application to show the mark in the form SharpIN, submitted a photograph of its packaging on which SHARP appears in light letters and IN appears next to it in dark letters, and requested the Examining Attorney to reconsider his refusal of registration.

The Examining Attorney accepted the amended depiction of the mark but denied the request for reconsideration, and the applicant appealed. The applicant claimed that when the Examining Attorney accepted the amended drawing of the mark, he should have amended the application to indicate that the mark was shown in a special form. The applicant further claimed that it had discussed its proposed amendment with the Examining Attorney and that if he had any doubt about whether the applicant wanted to claim stylization as a feature of the mark, the Examining Attorney should have sought clarification from the applicant.

The TTAB disagreed. Under the USPTO's rules a standard-character mark may be shown in all uppercase letters, all lowercase letters, or in any combination of upper- and lowercase letters. So although amending the drawing from SHARPIN to SharpIN was acceptable, that amendment did not make the drawing a special-form drawing. Moreover, when making the amendment the applicant could have selected the "special form" option but did not do so. Thus, the TTAB said, the Examining Attorney had no reason to inquire whether the amended drawing was intended to be a standard-character or a special-form drawing. The TTAB said that the applicant's characterization of its amendment as a non-material change to the mark supported the TTAB's conclusion.

The TTAB then turned to the issue of whether SHARPIN is merely descriptive and therefore unregisterable on the USPTO's Principal Register. The TTAB noted that, contrary to the applicant's argument, "[t]he question is not whether someone presented with only the mark could guess what the goods or services are. Rather, the question is whether someone who knows what the goods and services are will understand the mark to convey information about them'" (citing DuoProSS Meditech Corp. v. Inviro Med. Devices, Ltd., 103 USPQ2d 1753, 1757 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (quoting In re Tower Tech Inc., 64 USPQ2d 1314, 1316-17 (TTAB 2002)) (other citation omitted).

Applying that test, the TTAB readily concluded that SHARPIN is descriptive of the applicant's goods. According to the TTAB, the mark "SHARPIN evokes an immediate association with the phonetically identical and otherwise virtually-identical word 'sharpen,' and there is nothing incongruous about the use of the word sharpen (or its phonetic equivalent SHARPIN) to describe the function of [the applicant's] goods." The TTAB rejected the applicant's argument that its mark is a double entendre, saying that the applicant's briefs make clear that the possible meaning of SHARPIN as "a sharpener . . . built within the knife block" requires the mark to be shown in the special form SharpIN, and "that is not the form of the mark for which Applicant seeks registration."

Thus, the TTAB concluded that it had "no doubt that a consumer who understands the relevant goods to be 'cutlery knife blocks which incorporate built-in sharpeners that automatically sharpen knives' will understand the SHARPIN mark to convey information about them" (citing DuoProSS, 103 USPQ2d at 1757). For that reason the TTAB affirmed the refusal to register the applicant's mark.